Over the past 12 years, we’ve seen a lot of proposals at OST, so let’s take a minute to reflect on the definition of a proposal and how you can make your proposals better. At its core, a proposal is a sales document, regardless of whether the recipient customer is federal or commercial. A proposal’s purpose is to persuade the reader to buy your product or service.

The keyword here is persuading. A proposal is not a technical treatise or dry list of blow-by-blow responses to requirements. Proposals can be highly technical and they must be responsive, but proposals need to clearly explain what we are going to do, how we are going to do it, and the value of our offering that justifies the price we are charging.

With that said, most proposals bore the reader to tears, annoy them through excessive bragging, or insult them by explaining things they already know. They fail to dazzle and persuade. How can you make your proposals more persuasive and raise your probability of winning (Pwin)?

Proposal Evaluators are Emotional Buyers

One of the tenets of writing persuasive proposals is understanding that people are emotional buyers. They make a quick emotional decision and use logic and reason to justify the emotional reaction. Customers have two drivers: thedesire for gain and thefear of pain,such as risk of failure. The fear of pain is stronger than the desire for gain.

Your proposal needs to satisfy these opposing drivers by thoroughly laying out the benefits of your solution to satisfy the desire for gain. At the same time, the proposal needs to present a clear technical plan, effective management controls, and past performance to prove your claims from the perspective of well-articulated risk reduction, which will alleviate the fear of failure. Sometimes you may even consciously stir up the fear of pain more if you know how your competition could fail due to the complexity of the work.

The tricky part is understanding and focusing onour customer’s ambition and pain because we tend to sell what we have, instead of what our customers need. We justify this behavior by making self-centered assumptions that our clients need what we offer. Proposals at their core must be about your customer, not your offerings.

Start with Understanding Your Customer’s Hot Buttons

To achieve deeper customer understanding, we must learn the “key drivers” behind the requirements, also known as “hot buttons.” A hot button is your customer’s hope, fear, or bias about such elements as:

- Cost, risk, or schedule

- Technology used

- Compliance with regulations

- End user satisfaction

- Quality

- Public welfare

- Leaving a legacy

- Competitive positioning

- Thoroughness

- Formality

- Innovation

- Reputation

- Politics

- Career and personal goals

- Organizational goals and priorities

- Etc.

If proposals are all about our customers’ ambitions and fears, then the natural question is, “How do you find that information?” You start with a lot of research and talking to people who work with your customers. Ideally, you want to interview those who have achieved customer intimacy. The process for finding this information in the federal world is part of what’s called “capture” and in the commercial world it’s called “presales.” You need to brainstorm across the entire set of requirements with subject matter experts (SME) who know your product or service and those people who understand the customer’s key drivers and hot buttons.

Defining Hot Buttons Leads to Developing Proposal Win Themes

Your goal is to define the customer’s wishes and vision and then craft a solution that delivers the vision, which requires a lot of thinking and planning. In the proposal, the outcome of this matching of hot buttons to your solution is called proposal themes, or win themes. Win themes use targeted features and benefits to create a clear value proposition, showing that if a customer buys from you, you will deliver their precise vision of success. You present this information with overwhelming proof and clear facts that build confidence and credibility in your claims of being better, faster, cheaper, or less risky.

Include Stories and Visual and Written Metaphors

Customer-focused content is the core of persuasion, but it’s not enough. Including stories of when your people went above and beyond and adding visual or written metaphors make proposals interesting to read. Metaphors create a mental picture that’s worth a thousand pictures. The metaphor works when your customer may not quite understand the value of some aspect of your offering.

For example, you may worry that your customer won’t understand how important it is to add a key step at your process’s start, that may cost a bit extra and take longer, but in the end, cuts down risk significantly. This technique works well to “ghost” your competition by contrasting how you know to take the right precautions while they may not. Your proposal could explain that this step is like a safety briefing aboard a ship – it may take extra effort and time, but will save countless lives in an emergency. This metaphor would be especially poignant if you wrote a proposal to a Navy customer or a cruise ship operator. They would instantly understand and get a vivid mental picture of how important is the process step you describe.

Mind the Proposal Flow and Readability Statistics

Presentation and readability of your proposal matter as well. The best proposals are easy to read and understand. You may have heard of the bottom line up front (BLUF) method, or colloquially, “tell ‘em what you’re going to tell ‘em and move on.” In the proposal world, we refer to this as the “journalistic method of writing,” which means you start with the main point and provide the supporting details after that. This method is opposite from the “scientific method of writing” many of us learn in college, which presents the supporting details first and leads to the logical conclusion at the end.

Proposals should be written at the 11th or 12th-grade reading level for technical volumes, and the 9th or 10th-grade reading level for all other sections. For reference, Abraham Lincoln’s eloquent Gettysburg Address was written at the 6th-grade reading level. For our proposals, we want to use the customer’s language, average 4-5 sentences per paragraph, average 20 words per sentence and write in active voice (subjects performing actions).

Invest into Professional Proposal Graphics and Layout

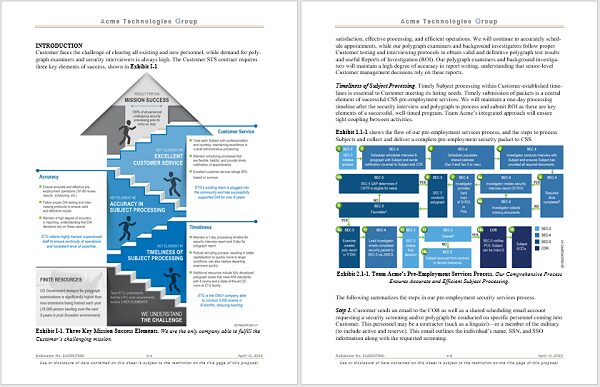

Proposals should also look attractive and professional by incorporating modern graphic styles and a visually appealing layout of the document. Graphics need to carry a message, not just be there because your proposal needs illustrations.

Proposals should also look attractive and professional by incorporating modern graphic styles and a visually appealing layout of the document. Graphics need to carry a message, not just be there because your proposal needs illustrations.

An effective proposal layout uses the unfortunately named C.R.A.P. principles of design, where C stands for Contrast (and the right use of color), R stands for Repetition where you use similar design elements throughout your proposal, A stands for alignment, to ensure that all elements on the page are aligned in relation to each other, and P stands for Proximity, where the similar elements are grouped together.

Make it Easy for Evaluators to Award the Proposal to You

Evaluating proposals is somewhat like evaluating resumes. If you have 20 resumes to read, you will throw out the ones you don’t like right away, skim the rest, and only really read the ones that have the best technical merit, are free of errors, and look the best. Don’t give your evaluators a reason to throw your proposal in the lost pile from the outset.

Being able to consistently produce persuasive proposals that sell is a sign of a great company. If you put time and effort into creating a customer-centric proposal, your customers are likely to assume that you will put as much care into project delivery. Reach out to our proposal experts at OST Global Solutions if you want to know how to improve your proposals and increase your Pwin.

Contact us to learn more.